There’s a lot of pressure on the (hopefully) first season of The Sandman. The show had to cover the first two major arcs of an iconic comics series, introduce dozens of new characters, and multiple fantasy realms, all while finding a consistent tone in a story that starts as a series of episodic chapters before turning epic, and starts as horror before turning into fantasy. (They also had to ditch a bunch of DC Comics continuity.) And, just as the comics had to do back in the ‘80s, the show needed to find a way to keep people invested after the bloody meatgrinder of John Dee’s visit to the 24-hour diner.

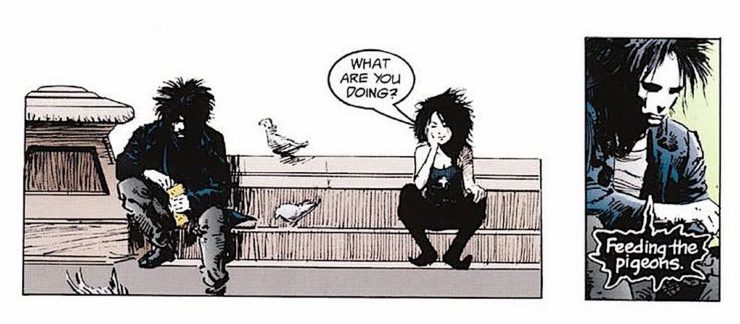

In the comics run, Issue #8, “The Sound of Her Wings”, is when The Sandman becomes The Sandman. It reestablishes the story’s theme, gives us new empathy for Dream, and introduces Dream’s sister, Death. It’s also a nigh-perfect issue, a compact jewel of a story that feels enormous. So in the midst of the pressure to get The Sandman as a whole right, the episode that adapted “The Sound of Her Wings” needed to capture a certain spirit to lead viewers onto solid ground, and send them off into the second half of the season.

I think Episode Six does this beautifully well, and it does it through tiny choices in adaptation.

“The Sound of Her Wings” is practically perfect in every way. In the context of The Sandman as a whole the issue is the turning point when the series shifts from horror comic to dark fantasy. It shows us a new side of Dream—instead of a vengeful escaped prisoner or the Forbidding Lord of a Terrifying Realm, he’s now a mopey little brother. After hearing hints of other Endless, we finally meet one of them, and get a sense that this is a large, fractious family that functions more or less like a human one. And the one we meet is Death.

Death’s introduction is, let me make clear, astonishing in context. This is an all-powerful entity who’s also a girl in black jeans and a tank top. This is a girl in a comic in black jeans and a tank top. This is a girl in a comic who isn’t a D-cup in spandex. This is a girl in a comic who gently takes the steering wheel from the comic’s protagonist and proceeds to drive all the action. This is a Death who looks like a person, not a skeletal reaper. This is a Death who is warm and funny. This is a Death who carries a symbol of eternal life rather than a scythe. This is an Endless who chose not to interfere when a fellow Endless was imprisoned. This is a sister who’s worried about her brother’s depression. This is a sister who abandoned her brother to his fate. This is the sibling who, alone of their siblings, has shown up to help him pick up the pieces.

The issue itself is not a typical late-80s comic. There’s no self-conscious edginess, no capes, no proliferation of pouches—and all the necessary hands and feet are fully rendered on the page. But it’s also not fully in the indie realm of a Box Office Poison or a Strangers in Paradise, of confused young people talking through their romantic foibles (and occasional mob entanglements) against a background of coffeeshops and ramshackle share houses. The only pop culture references come up in Death’s love of Mary Poppins, and a fragment of a stand-up routine about Batman, tragically cut short by a faulty mic. This comic is earnest, heartfelt, immediate, there is not a drop of irony in its blood. It has a plot, and that plot is that you, and Dream, are going to watch a lot of people die in a lot of different ways.

Here are the deaths we see in the comic:

- A person dies of old age

- A person dies by electrocution

- An infant dies of unspecified causes

- A person drowns

- A person is shot in an alley

- A person ODs

- A person dies in a hospital bed

- A person jumps, or is pushed, from a rooftop

- A person bleeds out at the foot of a staircase

- A person is hit by a car

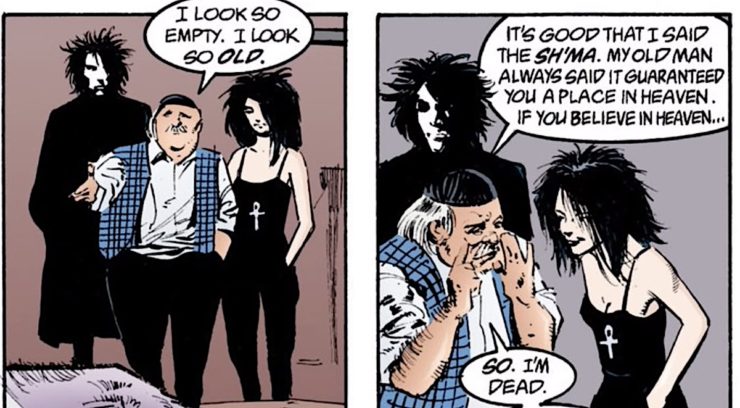

Only the first three and the last one are given space to speak—the old man says the shema, the electrocuted comedian mourns the career she might have had, the baby asks if this is all the life they get, the person hit by the car, Franklin, has already flirted with Death and tries to pick up the flirtation with no idea of what’s happened to him. The others are presented as a torrent, pebbles in a landslide, to show us the full weight of Death’s job.

Rather than experiencing death from the dying peoples’ perspectives, we’re watching Death collect them from Dream’s point of view. It soon becomes clear that Dream is baffled when people resist his sister’s gift. He recites a passage from an Egyptian text, “The Dispute between a man and his Ba”:

Death is before me today:

like the recovery of a sick man,

like going forth into a garden after sickness.

Death is before me today:

like the odor of myrrh,

like sitting under a sail in a good wind.

Death is before me today:

like the course of a stream;

like the return of a man from the war-galley to his house.

Death is before me today:

like the home that a man longs to see,

after years spent as a captive.

In the original text, these words are being spoken by a soulsick man who wants to die so he can go to the afterlife. His Ba, the personal part of the soul in Egyptian teaching, tries to talk him out of it. (Which, well, if you know the arc of The Sandman, it’s extremely interesting that this is where Dream’s mind goes as he walks with his sister.) And while Dream certainly sees people a little better after this day, and seems reinvigorated by it, he also isn’t exactly meeting the dying people on their own terms—rather than engaging, he hangs back and meditates on an Egyptian suicide note.

Because again remember: most of these are violent deaths. The only two that match the tone of Dream’s recitation are Harry, the elderly Jewish man who accepts that his time has come, and, possibly, the man in the hospital, who may see Death as a release from illness. The rest are conspicuously younger people, going out in violent, unexpected ways. And then there’s the baby, who seems to accept their fate after a brief argument—but then we have to watch the mother scream and collapse to the floor a panel later.

If you read the collections, this issue is either the light at the end of Preludes and Nocturnes, with its hellish diner and actual Hell, or the drawn breath before the trauma and serial killers that stalk through The Doll’s House. “The Sound of Her Wings” stands apart, a pocket that I always remember as calm despite the body count.

In this way, “Men of Good Fortune” serves as its mirror. The issue comes in the dead center of the arc that’s collected in The Doll’s House—whether you were reading the series in real time, or reading a complete collection, the effect is incredibly jarring: Morpheus blows up the house where Brute and Glob have been holding Jed Walker hostage. Jed escapes only to be picked up by The Corinthian. Morpheus banishes his renegade Nightmares and dispatches Hector Hall to whatever afterlife awaits him; Lyta Hall, who had no idea her husband had been dead for two years, thinks Morpheus murdered him. The Dream Lord comforts her by announcing that her child is actually his, and that he’ll find her later when it’s time to take the baby away.

We leave poor traumatized Lyta in a state of shock and poor traumatized Jed riding shotgun with a literal waking nightmare. Turn the page and—we’re in England, in 1389.

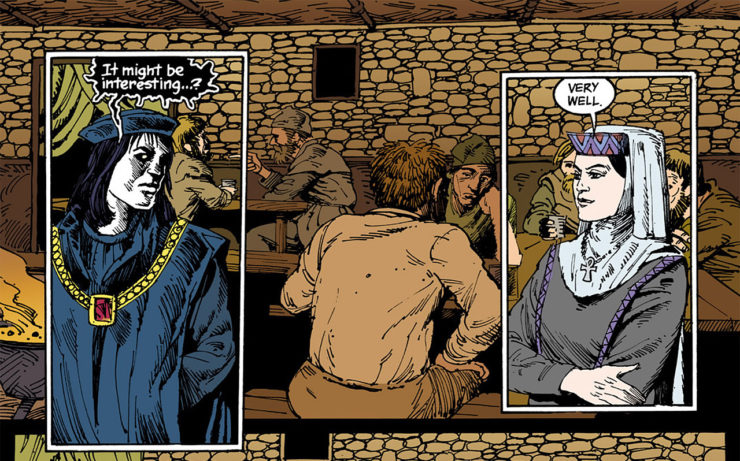

Morpheus has just been dragged to a tavern by Death. She thinks that he needs to walk among humanity to understand them better. Once we adjust to being thrown back in time, we see that this is a longstanding argument between the siblings. Dream regards the humans with barely concealed disgust, only slightly perking up when he sees Geoffrey Chaucer. But before he can strike up a conversation with Geoffrey, he overhears Hob Gadling announce his plan not to die.

“Men of Good Fortune” skips through time from 1389 to 1989, dropping in on Morpheus’ once-a-century meeting with Hob. We watch fashions change and food improve as humanity mostly stays the same—furious about taxes, angry about politics, convinced that every new illness or weather pattern is a sign of the end times. (OK, sometimes we’re right about that.) Hob doesn’t really change, at least not for the first few hundred years: his fortunes improve, sour, and improve again; he falls in love, but outlives his wife and children; he throws himself into new business opportunities enthusiastically but without real moral consideration. It’s Dream who changes, if only in tiny, glacial increments, until by the end, and only after a ridiculous temper tantrum, Dream of the Endless admits he’s made a human friend.

If there was any Job-like long game happening here, Death has emerged victorious with a slightly more empathetic brother.

In the comic this issue serves as a slight corrective to the disastrous scene with Lyta Hall, and, like “The Sound of Her Wings”, a chance for us to catch our collective breath before we get to the Cereal Convention. It also prepares us for the ending of the arc, when Dream knows he has to kill Rose Walker but can’t stop apologizing long enough to do it. As horrible as he was to Lyta, he is not the cold, alien creature who regarded people with revulsion in 1389. The meetings with Hob have changed him, and his imprisonment has changed him.

Now when it came time to adapt these comics for the show, there were choices to be made. “The Sound of Her Wings” is, as I mentioned, perfect. But how do you bring perfection to the screen? What can you possibly do with it that will give it new life without hurting what you have on the page? And will a television/streaming audience, perhaps new to this story, come along on the leaps through time that “Men of Good Fortune” demands? Will they accept the interruption in the taut story of a girl searching for her missing brother, a pregnant woman mourning her husband, while a convention hall full of serial killers looms on the horizon?

“The Sound of her Wings” improved on the comic. First in the casting of Kirby Howell-Baptiste, who brings so much warmth and humanity to the part that you understand why Dream would be surprised that anyone resists her. I’ve noticed it in almost every review, actually: people specifically describe Howell-Baptiste as “warm”. Because Death isn’t like that, usually, for most people. For most people it’s a tangle of tubes and machines that go ping, nurses who are exhausted and exploited, maybe just hypothetically a front desk lady who refuses to pull her mask over her nose and keeps trying to prevent you from seeing your mom one last time.

Maybe that one’s just me.

(I hope that one’s just me, I don’t recommend it.)

Or, as in the comic, death is an accident, an act of violence, a drug that overwhelms you. Something that doesn’t give you time to say goodbye. And awesome as Death is, it’s kind of hard to convey warmth on the page—casting a person who seems like the human embodiment of the SUN is genius.

The other element that is even better is that instead of Dream intoning a pro-Death poem, we’re with the dying in a much more intimate way. The camera allows us to be in the point of view of the dying person, looking into Death’s welcoming face, or with Death herself, collecting people who are terrified, resigned, relieved. Rather than see this through Dream’s cool detachment and judgmental tone, the camera lets us check in on him occasionally during their day. Doing this allows the episode to be much more about the dying people and the entity collecting them than Dream’s drama. Death’s just doing her job, the people are coping with the last moment of their lives. The brief reaction shots he gets makes it clear that Dream can allow this to change him or he can hold himself apart—but none of this is about him.

(And here too, people have been unanimous in their love of Tom Sturridge, but I think he’s especially good in this episode. He conveys so much of Dream’s pain, fear, and growing empathy in tiny muscle contractions—just rewatch the scene with the baby.)

I did my best to keep myself unspoiled for the show. Beyond basic casting decisions like Jenna Coleman playing Johanna Constantine instead of John, and Vivian Acheampong playing Lucienne rather than Lucian, I didn’t know what they’d kept, what they’d changed, if any DC continuity stuff was happening, if they were holding off on some of the standalone issues for possible later seasons. I yelped out loud when Dream took leave of his sister and walked around to the pub looking for Hob.

This was when the episode really took flight for me. Because now, with this reordering, we see “Men of Good Fortune” in a new context. Here is Death, centuries ago, trying to get her brother to see the beauty in humanity, to open himself up to empathy and the kind of joy she finds in her job. This would be long after her own crisis, after all—the Death we’re seeing here isn’t so different from the one of “The Sound of Her Wings”. The action unfolds much as it does in the comic, with almost all the dialogue direct lifts. But there are a few crucial differences: Death is the one who nudges Dream into the experiment with Hob, and when he walks over to propose the deal, Death looks like nothing so much as a big sister watching her toddler brother head off for his first day of pre-school, hoping the other kids like him.

Two of the changes are with Hob: in 1589, when he’s married well and purchased a title, he is very openly trying to impress Dream. Where in the comics 16th Century Hob just seemed like he was making up for two centuries of shitty food, this one has clearly laid out a spread to wow the entity he already sees as a friend. When that entity literally waves him off to go talk to Will Shaxberd it’s actually heartbreaking. (After all, who else does Hob have to talk to? He can’t tell the lovely Eleanor what he really is; his old pub mates are bones and dust.) The second change comes in 1789, when Lady Johanna Constantine crashes their meeting. In the comics Dream enchants Johanna and both of her henchmen with his Sand. In the show Hob takes both henchmen out before Dream makes a move, and Dream only enchants Johanna when she has a blade at Hob’s throat.

As Hob realizes that Dream doesn’t need his protection, Dream realizes that Hob defended him without hesitation. After 400 years, Dream finally extends genuine care to Hob—for his physical safety, yes, but more important by rebuking him for engaging in the slave trade, which he does with much more force than in the comic. (If Dream wanted this to be a pure experiment he could hang back and watch what the ants do to each other, right? And something as horrific as the Mid-Atlantic slave trade would only justify his old disgust for humanity.) But instead Dream steps in, and points Hob’s hypocrisy out to him, because he’s begun to care about the choices he makes. Is it any wonder that Hob calls him a friend at their next meeting? And Dream, for his part, opens up about Lushy Lu’s history, showing Hob both his own near-omniscience and the deep well of empathy he actually has for people. He even seems to want to accept Hob naming him as a friend—until Hob calls him lonely.

And finally the biggest change.

The decision to pair “Men of Good Fortune” with “The Sound of Her Wings” means that his day with his sister can spill straight into his reunion with Hob. The decision to move the present action from 1989 to 2021 means that he missed their last meeting—and that opens a whole other possibility. In the comic we see Hob sitting with his Gordon Gecko hair, listening to people’s musings on Thatcher’s taxes and the AIDs pandemic, smoking a cigarette and nursing a beer. He seems surprised when Dream finally shows, but since we only see a couple panels of his wait, we have no idea how long he was sitting alone. In the show we watch as he waits… and waits… and waits. We know Dream isn’t gonna show, and we know why. But Hob has to assume that their last meeting was truly their last.

And what does he do? He waits all day. And when he learns that the ancient pub is going to be razed he (because who else could it be?) leaves a childlike red arrow pointing to The New Inn around the corner. And he goes to that pub and waits. And thirty-three years go by, but he keeps showing up.

And this is where this edit is really brilliant.

In the comics chronology Dream conducted the experiment with Hob as usual in 1889, got himself captured in 1916, had about 7 decades to meditate on whether or not he was actually lonely, escaped in 1988, had his day with his sister, recommitted to his work and purpose, and then, presumably at some point after that, turned up for his usual meeting with Hob in 1989, a slightly wiser immortal being.

In the adaptation, he’s forced to miss the meeting. He forgets about it, in fact, so hung up on vengeance that he immediately forsakes his realm again. It’s not until the day with his sister that he starts to remember what’s important to him. And where, in the comic, Dream watches his sister work and remembers how much he loves his job, here his day with Death strikes him in a slightly different way. Watching human after human fight for a few more moments of life, watching human after human collapse into grief as he and Death walk away, he remembers a person he cares about, not just a task. His work as Dream is inextricably woven into the empathy he has for humanity. By weaving “The Sound of Her Wings” and “Men of Good Fortune” together, the show makes Death’s love of her brother all the clearer, and it also gives us a Morpheus that is, gradually, learning how to love people on their terms rather than his. Which, if the series continues, could make for a very different version of The Sandman.

I keep thinking about this. I haven’t quite gotten at what makes this hour of television so special. I said up top somewhere that “The Sound of Her Wings” had a particular spirit that set it apart from most comics, and I think that’s what I’ve been circling. “Men of Good Fortune” didn’t have that spirit—it was a fun short story that ended up meaning a little bit more, but readers of The Sandman soon got used to short stories and digressions, and cameos from characters like Shakespeare, the fae, and Emperor Norton. By shifting the focus of “The Sound of Her Wings” more onto Death’s journey, and the people themselves, it brought the feeling of that issue into better focus. And I think that weaving it into “Men of Good Fortune” took that story and made it sharper. Just as the episode shifts the focus onto Death, “Men of Good Fortune” becomes more about Hob Gadling befriending Dream than about Dream’s loneliness. And on top of that, creating a direct link between the two stories makes it clear that Hob’s story isn’t about rejecting Death—it’s about savoring life. When Dream finally comes to his senses and realizes that yes, Hob is his friend, he’s also realizing that, after more than a century of captivity, after his quest for revenge, he wants to live.

Which makes it a great launching point for the second half of the season, but, much more important I think, it makes it a perfect, joyful story, uniquely its own.

Leah Schnelbach agrees that death is a mug’s game. Come meet them every hundred years in the overcrowded tavern that is Twitter!